Measurement Bias in AI

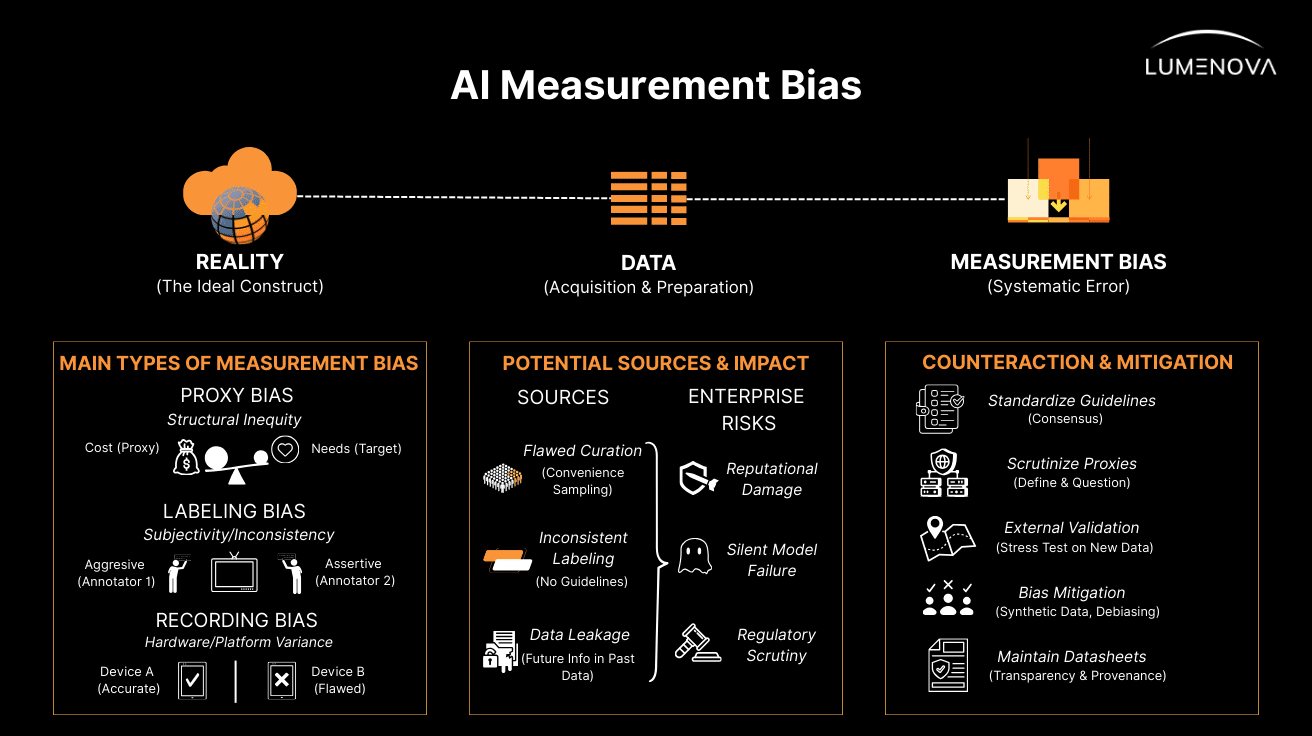

Measurement bias (often referred to as measurement error) is a subtype of AI bias referring to a systematic distortion that occurs when the data used to train an artificial intelligence model fails to accurately represent the real-world concept it is intended to measure. This type of bias arises not only from who is selected for a dataset, but also from how their characteristics, behaviors, or outcomes are recorded, labeled, or categorized.

For enterprises across sectors – from finance and recruitment to healthcare and logistics – measurement bias represents a critical risk. It embeds historical prejudices, subjective human judgments, and faulty proxies into the core of algorithmic decision-making. When an AI model is trained on data containing these measurement errors, it treats the distorted view as “ground truth”, leading to skewed predictions that can damage corporate reputation, invite regulatory scrutiny, and perpetuate systemic inequities.

What is Measurement Bias in the Context of AI?

In the context of Artificial Intelligence, measurement bias refers to the gap between the data an organization possesses and the actual reality that the data is supposed to reflect. It often stems from the reliance on “proxies” – observable variables used to stand in for complex, unobservable phenomena.

For example, an organization might use “historical hiring data” as a proxy for “candidate potential.” However, if past hiring decisions were influenced by human prejudice, the data measures past preference, not future potential. A notable instance occurred in 2018 when a major tech company’s recruiting AI penalized resumes containing the word “women’s” (e.g., “women’s chess club”) because the model had learned from historical data that male candidates were preferable.

Bias exists across the entire AI lifecycle, involving human, machine, and systemic factors. Measurement bias specifically manifests during the data acquisition and preparation phases, where inconsistent annotation, subjective interpretation, or flawed instrumentation can corrupt the dataset before a model is even trained.

What Are the Main Types of Measurement Bias in AI?

Measurement bias generally manifests through three primary mechanisms that affect organizations across all industries: Proxy Bias, Labeling (Annotation) Bias, and Recording (Instrumentation) Bias.

1. Proxy Bias

This occurs when a measurable feature is used as a stand-in for a target concept, but the proxy itself contains structural inequities.

- The Flaw: Developers often select a proxy that is easy to measure, assuming it correlates perfectly with the desired outcome.

- The Reality: If the proxy reflects systemic barriers, the model will codify those barriers. For instance, in healthcare, algorithms have historically used “cost” as a proxy for “health needs”, falsely assuming that lower spending equates to better health, when it often reflects a lack of access to care for underrepresented groups.

- Business Impact: In a commercial setting, using “zip code” as a proxy for “creditworthiness” can similarly encode redlining practices, denying services to qualified individuals based on location rather than actual risk.

2. Labeling (Annotation) Bias

Supervised learning relies on labeled data, which is frequently generated by human experts. When these experts apply subjective, inconsistent, or culturally biased standards, the AI learns these inconsistencies as fact.

- Subjectivity: In sentiment analysis or toxicity detection for Large Language Models (LLMs), what one annotator considers “aggressive” might be viewed as “assertive” by another, often depending on the demographic of the speaker.

- Inconsistency: When multiple annotators are used without standardized guidelines, inter-annotator variability introduces noise. If labels are applied unevenly – for example, if a “positive” employee review is harder to earn for one demographic than another – the AI will learn to undervalue that group.

3. Recording (Instrumentation) Bias

This bias arises when the tools, sensors, or platforms used to capture data perform unevenly across different conditions or groups.

- Hardware Limitations: Physical sensors may have varying accuracy depending on environmental conditions or physical attributes of the subject (e.g., biometric sensors performing poorly on darker skin tones).

- Platform Variance: In digital environments, data distribution shifts can occur simply because of changes in the software or hardware used to collect data (e.g., upgrading a CRM system or changing a camera vendor), which the AI interprets as a change in the real-world metrics.

Why Should You Care About Measurement Bias?

Ignoring measurement bias exposes enterprises to significant ethical, legal, and operational risks.

- Reputational Damage and Trust: Biased AI systems can lead to public failures that erode consumer trust. The Amazon recruiting tool example mentioned above demonstrates how bias can force a company to scrap a high-profile project to protect its reputation as an equal-opportunity employer.

- Silent Failure of Models: Unlike software bugs that cause system crashes, biased models often fail silently. They continue to generate predictions with high confidence, but those predictions are fundamentally flawed for specific subgroups. This can lead to discriminatory resource allocation or missed opportunities without triggering standard error alerts.

- Regulatory Compliance: Regulators are increasingly scrutinizing the total product lifecycle of AI. They expect organizations to identify and mitigate discrimination in data handling. Failure to do so can result in compliance violations, particularly as new frameworks for AI governance emerge globally.

- Feedback Loops: Measurement bias creates self-fulfilling prophecies. If a fraud detection model falsely flags a specific demographic as “high risk” based on biased historical data, that group will be subject to more scrutiny, generating more fraud data, which in turn reinforces the model’s original bias.

What Are the Potential Sources of AI Bias Impacting Model Performance?

To effectively mitigate measurement bias, organizations must identify its root causes within their data pipelines.

1. Flawed Data Curation and Convenience Sampling

Datasets are often curated from convenience samples – data that is easily accessible rather than truly representative.

- Geographic Bias: Research shows that many major AI datasets are sourced from a handful of geographic regions (e.g., specific states or tech-heavy cities), ignoring vast “data deserts”. This results in models that perform well for populations in those regions but fail when deployed elsewhere.

- Exclusion: Vulnerable or underserved populations are frequently missing from training data entirely, leading to underdiagnosis or service denial when the model encounters them in the real world.

2. Inconsistent Labeling Protocols

The absence of rigorous, standardized guidelines for data labeling is a primary driver of measurement error.

- Lack of Consensus: Without a gold standard or clear problem definition, annotators rely on subjective interpretation. In technical fields, using ”silver standards” (like raw reports or unverified logs) rather than confirmed outcomes introduces significant noise.

- Outsourcing Risks: Large-scale labeling often involves third-party groups. If these groups lack domain expertise or clear rubrics, annotator heterogeneity increases, and the quality of the ground truth degrades.

3. Data Leakage

Data leakage occurs when information about the target outcome inadvertently slips into the training data, creating a false sense of accuracy.

- The “Cheat Sheet” Effect: A classic example involves a prediction model where the input variables include a decision that happens after the event being predicted (e.g., including “antibiotic orders” to predict “infection”). The AI isn’t predicting the event; it’s just reading the human’s reaction to it. This results in models that look perfect in testing but collapse in production.

4. Large Language Model (LLM) Training Data

With the rise of Generative AI, measurement bias has found a new source: the internet.

- Unsupervised Learning Risks: Models like ChatGPT are trained on vast amounts of unstructured text from the internet (books, websites, social media). This data inherently contains the biases, stereotypes, and fake news present in online discourse. While developers attempt to filter this, the models can still inherit biased associations, such as assuming certain professions are gender-specific.

- Toxicity: Without careful curation, LLMs can learn and reproduce toxic or exclusionary language found in their training corpora.

How Can Enterprises Counteract the Effects of Measurement Bias?

Mitigating measurement bias requires a proactive, multi-stage approach, moving beyond simple accuracy metrics to a holistic view of data integrity.

Establish Standardized Annotation Guidelines

To reduce labeling bias, organizations must implement predefined, task-specific guidelines for data annotation.

- Standardization: Clear rubrics minimize human subjectivity. Before procuring third-party AI, companies should verify that the vendor’s labeling protocols align with their own internal standards to ensure consistency.

- Consensus Labeling: For critical datasets, using multiple annotators and a consensus mechanism (rather than a single individual) can help smooth out subjective errors.

Scrutinize Proxies and Definitions

Developers must critically evaluate the variables used as inputs.

- Proxy Analysis: Ask: Is this feature a direct measure of the outcome, or a proxy? If it is a proxy, does it correlate differently across different demographic groups? Diverse teams, including social scientists, can help identify systemic biases embedded in these metrics.

- Problem Definition: The definition of the target variable must be precise and agreed upon by all stakeholders to avoid objective mismatch bias.

Implement External Validation

A model often performs well on its training data but fails when the environment changes (distribution shift).

- Stress Testing: Enterprises should demand external validation – testing the model on a disparate dataset from a different region, time period, or demographic that the model has never seen before. This reveals whether the model has learned generalizable rules or just the idiosyncrasies of the training set.

Use Bias Mitigation Algorithms

Techniques exist to debias data representations directly.

- Synthetic Data: Methods like synthetic data augmentation can be used to oversample underrepresented groups, correcting class imbalances without losing information.

- Embedding Correction: For NLP applications, algorithms like Sent-Debias can remove stereotypical associations (e.g., gender roles) from word embeddings, ensuring the AI focuses on semantic meaning rather than social bias.

Maintain “Datasheets for Datasets”

Documentation is essential for governance.

- Transparency: Using frameworks like “Datasheets for Datasets” helps track the provenance of data, the motivation for its collection, and known limitations. This transparency allows downstream users to understand potential measurement biases inherent in the dataset before they deploy the model.

Detect and Counteract Measurement Bias with Lumenova AI

Measurement bias is rarely obvious; it hides in the metadata, the proxies, and the silent failures of edge cases. For modern enterprises deploying AI at scale, manually auditing datasets for these complex errors is no longer feasible.

Lumenova AI provides the governance and observability infrastructure needed to automatically detect measurement bias. Our platform enables you to:

- Evaluate Proxies: Analyze correlations between input features and sensitive attributes to identify biased proxies that may be skewing your results.

- Monitor Distribution Shifts: Automatically flag when real-world data drifts from training baselines, indicating potential measurement failures or concept drift.

- Standardize Validation: Implement rigorous testing protocols that ensure your models are robust across all demographic subgroups, preventing silent failures before they impact your business.

Don’t let measurement bias undermine your AI strategy. Ensure your models measure what matters – fairly and accurately.

Sources

Tejani, A. S., Retson, T. A., Moy, L., & Cook, T. S. (2023). Detecting Common Sources of AI Bias: Questions to Ask When Procuring an AI Solution. Radiology.

Gichoya, J. W., et al. (2023). AI pitfalls and what not to do: mitigating bias in AI. British Journal of Radiology.

Gray, M., et al. (2023). Measurement and Mitigation of Bias in Artificial Intelligence: A Narrative Literature Review for Regulatory Science. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Selection bias refers to who is included in the dataset (e.g., a dataset that excludes a certain demographic entirely). Measurement bias refers to how the data is recorded or labeled for those who are included (e.g., a system that inaccurately categorizes the behavior of that demographic due to flawed proxies or sensors).

Not necessarily. If the new data is collected using the same flawed proxies or biased labeling processes, adding more data will simply reinforce the existing bias – a phenomenon known as bias amplification. You need better (cleaner, more representative) data, not just more data.

Data leakage creates a measurement error where the model learns a shortcut rather than the actual pattern. For example, if a model sees data that shouldn’t be available at the time of prediction (like an outcome recorded in the input), it will measure that leak instead of the true predictive factors. This leads to falsely high performance estimates that do not hold up in reality.

Yes. Generative AI models are trained on vast datasets scraped from the internet, which contain human biases, stereotypes, and fake news. Without mitigation, these models measure and reproduce the statistical likelihood of these biases appearing in text, leading to outputs that can be stereotypical or toxic.

Rarely. It often stems from unconscious oversight, such as selecting a convenient proxy (like hiring history) without realizing it encodes historical prejudice. However, even unintentional bias can have severe legal and reputational consequences.